The Iron Industry In Crawley

(Created 29 Nov 2019. Last updated 16 Jan 2023)

A history of the town's 2,400 year old Iron Industry

and a look at the surviving features.

Illustrated with 141 images & 18 maps

By Ian Mulcahy

Iron Age & Romano-British | Medieval | Tudor and beyond

|

With it's clay and sandstone geology providing a local source of iron

ore and building materials and a copious amount of woodland providing

fuel, Crawley has a relationship with the iron industry which stretches

back over 2,000 years and much evidence of this relationship still

exists within the town, some of which is visible and some of which is

hidden away under new town developments. The earliest evidence of a

local iron industry dates back to pre Roman times and has been found at

a series of linked sites forming a significant domestic and industrial

settlement in Southgate and Broadfield. Beyond hard to read academic

papers, this period has a story that has never really been told before

This is the history of iron working in the Crawley area. Iron Age & Romano-British Goffs Park | Southgate West | Broadfield Goffs Park: When a large house known as 'Springfield', on the Horsham Road, was demolished to make way for what is now Goffs Close the site was subjected to an archeological examination. During the excavations, carried out in 1970, two ditches were exposed which "contained great quantities of bloomery slag, roasted ore, charcoal and pottery". The pottery was dated to somewhere between 50 b.c. and 43 A.D and aerial photography revealed two circular rings between the ditches. It is thought that these markings showed the remains of dwellings, possibly hut circles. The iron was manufactured in a type of furnace known as a cylindrical shaft furnace and radio carbon dating showed that the 2 furnaces discovered dated back to 60 b.c. & 190 b.c. which, as of 1992, were the oldest of their type yet discovered in the UK. As well as manufacturing iron, it is possible that this Iron Age industrial & domestic settlement was used for the production of pottery. The Goffs Park site was probably abandoned with the residents and industry moving across to the already existing Broadfield sites (see below), soon after the Roman invasion of 43 A.D. Southgate West: Some 500 metres to the south of the Goffs Park site is Hilltop Primary School in Ditchling Hill, Southgate West. During the construction of the neighbourhood, again in 1970, a 300 metre long V shaped ditch was discovered which followed the path of what is now Caburn Heights and curved round to the north, ending where Captains Walk now is (see map below). Within the ditch, artefacts that could be dated to the 1st, 2nd & 3rd centuries were recovered and the excavation director, Mr J Gibson-Hill, suggests that the ditch represented the south and west sides of an enclosure which was centred on what is now the school.

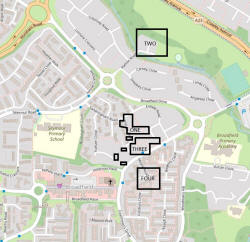

Further excavations, carried out between 1970 & 1973, discovered a settlement covering an area of approximately 20,000m2 with domestic settlements in the centre surrounded by ore workings. Among the finds were ore roasting and forging facilities, smelting furnaces, a water reservoir, a puddling pit (used in pottery and brick making), a blacksmiths workshop with a fitted stone built forge, slag dumps and a 55m2 building which is believed to have been a workman's building. Archaeologists examining the site were not given the opportunity to extend their dig as development was going on all around them, but some believe that, outside of the area that was examined, a small village of up to 50 dwellings could have existed. The evidence of this, if it exists, will now be buried under the houses and flats of Southgate West. Mine pits were also discovered in the small area of woodland to the south of Hindhead Close. Broadfield: In Broadfield, significant evidence of Middle to Late Iron Age and Romano-British iron workings, possibly dating back as far 370 b.c., was found during archaeological digs coinciding with the setting out of the estate and the installation of utilities. Four separate sites were found and these were, using contemporary descriptions:

Here is a modern map showing the rough positions of the sites excavated. Site one was predominantly an industrial area and finds here included over 20 furnaces, some of which were arranged along both sides of a 16.5m long ditch filled with slag which terminated in a 5m diameter pit at the southern end of the site. It is believed that the ditch and pit were some form of reservoir used to provide a supply of water for the iron smelting process. Also found was a 2.3m by 1.3m forging hearth surrounded on three sides by sandstone blocks and contained within the remains of a small timber framed building, open on three sides with the northern side enclosed with a wattle screen. Industrial activity at site one ceased in the early part of the second century. Site two was home to the earliest evidence of iron workings at the Broadfield sites, dating back to between 190 & 370 b.c. and discovered in the south western area of the site close to Broadfield Brook. Also unearthed in this area, protected from disturbance by a layer of soil, furnace slag and the collapsed remains of a furnace were plough marks in the clay that pre dated the industrial workings and were, as of 1992, the earliest found evidence of arable farming in The Weald. Farming, of course, indicates settlement so we can conclude from this evidence that humans had set up home within the current boundaries of Crawley at least 2,400 years ago. Also at site two, from a later phase of the sites use (probably from 43 to 73 A.D.) and enclosed within a ditched and banked area of approximately 100m by 80m, were found several domestic buildings. The foundations and a handful of courses of sandstone blocks of these buildings were protected by a layer of furnace slag. Also within the enclosure was a hard standing area of 27m by 21 made up of slag and furnace debris which showed signs of repair to wheel rutting. This was most likely used to park wagons; an ancient car(t) park! 26 uniform & circular post pits just to the south of the hard standing area marked out a timber framed building of 15m by 7m. Close to Broadfield Brook was a 15m by 8m building, marked by 14 square post pits and in the floor of this building was a horseshoe shaped domestic oven. It is thought that the domestic use of this site lasted for 20 to 30 years from the time of the Roman invasion of 43 A.D. after which the superstructure was demolished, most likely in order to expand the industrialisation of the site. A minor find, discovered when the Brook was straightened in 1973, is thought to be a pottery kiln. In all, some 26 furnaces of varying types and ranging in age from 370 b.c. to 110 A.D were discovered at site two. Several mine pits were also located to the north of the area in what is now the wooded area between Broadfield Brook and the old football pitches at Rathlin Road playing fields.

A little way to the north west, in the area that remains as woodland and

wetland, a small mound was excavated and was confirmed to be a slag

heap. To the surprise of the archaeologists, two further furnaces

were found on top of the spoil and one was found to be relatively well

preserved. The furnace was lifted and taken to the Sussex Archaeological

Society's museum at Lewes for restoration before being moved to the

Science Museum for display in their, then new (1975), 'Historical

Metallurgy Gallery'.

A further investigation, undertaken subsequent to the closure of the Rathlin Road Playing Fields Pavilion and prior to the development of the flats that now occupy part of the site, unearthed fragments of Iron Age and Roman pottery and a further ditch containing charcoal which was carbon dated to between AD 984 and AD 1043, demonstrating that the site saw probable activity in the late Saxon period. This could have been as a result of iron smelting, but consideration must be given to Saxon scavenging of the site for slag to use as hardcore.

Site three was originally, in the first or second century, a domestic site and on the eastern side of the site a domestic hearth was discovered. In a ditch next to it, which ran through sites one, three & four, domestic rubbish and building waste, such as tiles and nails, were found. The site was soon given over to industrial use and five furnaces were found here, one of which had a surviving wall of over 40 cm high and another had a surviving sandstone shaft of 76 cm. It is probable that these remains are now buried under the houses at the southern end of Lambeth Close or Lewisham Close. Site four dates back to about 30 A.D. and was developed as a replacement for the domestic dwellings at site two when they were demolished in favour of industrial expansion. Evidence was found for two houses, a granary and two domestic hearths. Just outside of sites 3 & 4, to the west, evidence of other buildings was found in the form of areas of burnt clay which would have been the flooring of the house, but these had substantial damage caused by ploughing in the centuries following the sites abandonment. 2 furnaces were found at site four. It is thought that the sites in Goffs Park, Southgate West & Broadfield, covering a total area of up to 120,000 m2, formed one large connected site rather than a series of separate works and would have been one of the largest iron producing sites in the region. Visual evidence of site 2 is still in existence for anyone who looks closely enough. The images below show two pieces of heavy Roman era furnace slag, one piece is in situ where I found it on the northern bank of Broadfield Brook and the other is placed for a different angle of photo. If you want to find some for yourself, the northern bank of the brook between the playground and the new flats at the end of Rathlin Road is rich in 1,600-2,000 year old industrial waste.

Little evidence of a Medieval iron industry in

Crawley survives, but a few little glimpses into the past have been

found hidden away, mainly in the town centre, during archaeological

excavations undertaken ahead of building works.

Many of the finds were just furnace waste and pottery which were most

likely brought to the site and used as foundations and flooring (such as

the waste found at the Old Punch Bowl and the barn that was situated

behind The Tree House) rather than created on the site. I have not

included these, electing to concentrate only on sites where evidence of

iron working exists.

Furnaces & Forges of the Tudor period and beyond

Tilgate Furnace | Tinsley Forge | Bewbush Furnace | Ifield Forge | Hyde Hill site | Worth Furnace | Blackwater Forge | Hammer Mead | Rowfant Forge The next major period of iron working in the town, and one that has left us with a wealth of surviving features and evidence, began in approximately 1546 during the Tudor period and coincided with technological advances which harnessed the power of water to drive the bellows and hammers of the blast furnace. The blast furnace was developed in China before the Roman occupation of England, but the technology did not arrive on our shores until it was introduced by skilled immigrant workers from northern France. This new type of furnace could produce a daily output of close to a tonne of iron, compared the few kilos produced by the old style bloomeries and so was a massive boost to efficiency. Across the Crawley area streams were dammed to create ponds and some of these, such as those at Tilgate, Ifield & Rowfant, still exist today. Others have had their dams breached and have reverted to being streams, but evidence of their past can still be seen in the form of bays (the term for the dam) and industrial waste scattered in the streams and surrounding area. The last water powered ironworks in the Crawley area closed in around 1736 and the demise of the local industry occurred because the whole area had been stripped bare of the timber required for the furnaces. By this time, iron working had started to shift to the north of the country where a plentiful supply of coal existed. The set up was relatively simple. A stream would be dammed at an appropriate point to create a pond and a sluice gate would be added to control the flow of water over a wheel, usually via a wooden race. The turning water wheel would power either bellows or a hammer; the bellows being used to add oxygen to the furnace to increase its heat and the hammer being used to work the iron. Generally, the forge and the furnace would use separate ponds in close proximity to each other. Often the working pond, if relatively small or shallow, would have a supply pond where further water could be stored to top up the furnace or forge pond in dry periods when it was not being replenished naturally. The use of pen ponds is best seen at Tilgate, where Tilgate Lake as we know it today was the pen pond for the furnace a third of a mile downstream. The furnaces were typically stone or brick built into a cone shape, covering an area of perhaps 24sq ft (2.25sq m) and standing up to 30ft (9m) high. The egg shaped cavity, perhaps 3m high, inside of the already ignited furnace would be loaded with a mixture of roasted ore, charcoal and a flux material* and a pair of huge water powered bellows would force a continuous blast of air into the column of ore and fuel, superheating the mixture and melting the ore. At the mouth of the furnace would have been a bed of sandstone where the iron would be cast into moulds; the resultant lumps of iron were known as ‘sows’ and ‘pigs’. These names derive from the practice of the sandstone mould having a large long channel down the middle, along which the molten iron would flow, with several smaller channels at right angles so giving the appearance of a sow feeding her little piggies! It could also be pored into moulds at this point to make specific items such as tools and weapons. Make no mistake, this was dangerous work that didn’t have the health and safety regulations, protective clothing or tools that we take for granted today. A furnace such as that at Bewbush would have produced somewhere in the region of 8 tons of iron every 6 days, using 24 loads of 11 quarters of charcoal and 24 loads of 18 bushels of pre-roasted ore. A quarter is 28lbs (12.7kg), but a bushel measures volume so it is hard to give an accurate weight, but it’s likely that a bushel of ore would have weighed somewhere in the region of 105lbs (around 47.5kg), so each load would have weighed 1,890lbs (850kg) and each 6 day blasting session would have used over 20 tonnes of ore and 3.3 tonnes of charcoal! Rising to the top of the molten mixture would have been the slag; the glassy carbonated waste product and this waste would have been drawn off sporadically and dumped nearby to cool down. *With the advent of blast furnaces iron masters were searching for ways to increase the purity of the iron by reducing the viscosity of the slag; a mixture of charcoal, ash, flux and molten non-iron elements of the ore which rose to the top of the furnace as a result of the heavier molten iron sinking to the bottom, where it would flow into the casting channels. A common flux material was limestone and the local source for use at Bewbush is evident - the high ridge on Ifield Golf Course is a limestone seam and the ridge is littered with pits and quarries. See the Ifield Golf Course map on my 'Non-designated Heritage Assets West of Ifield' Page for more details. A further rising ridge of limestone runs westwards from the mill at Ifield straight though the pit to be found west of the Millhouse, Dobbins Pond, the pits (1 remains, 2 are lost) in Stoneycroft Walk and the pond at Upper Bewbush Farm. It is inconceivable that these were not also limestone quarries.

In the Crawley area, we had at least three confirmed furnaces and four confirmed forges, with a probable fifth. I have visited all of the confirmed sites and the history of these, along with a look at what remains to be seen today, can be read below.

Having had a whole neighbourhood named after it (Furnace Green), Tilgate Furnace is probably the most well known site in the town. The furnace itself was located roughly where Furnace Farm Road meets St Leonard's Drive, with the pond that powered it being just to the south and south west in the area that is now Linden Close, Longview, Rillside, Forest View etc.

It is almost certain that the pond was significantly larger than that shown above when it was serving the furnace, stretching west along the low lying land of Weald Drive towards the playing fields at Loppets Road and Gainsborough Road and possibly to the north too across the Newmarket Road area. The pond had almost completely disappeared by the end of the 19th century. The furnace at Tilgate first came into use in 1588 and continued to be worked until 1685, with a brief spell of apparent 'downtime' between 1653 & 1664. Until the early 1640's the iron produced at Tilgate was taken to Holmsted Forge, just south of Staplefield, for processing. Around this time, Walter Burrell, the then owner, entered into a partnership with Leonard Gale and the Tilgate iron was then sent to the forge owned by Gale at Tinsley Green (see 'Tinsley Forge', below) using a route that many commuters in the area use today in order to get to Three Bridges station every day, that is along Tilgate Drive, also known locally as 'Black Alley'. The carts would have then followed the route of North Road & Tinsley Lane. It is interesting to note that Maidenbower Lane, which still exists as the path under the railway by Oriel School, linked the Tilgate Furnace site with the forges at Blackwater Green and Hammer Mead (see 'Blackwater Forge' and 'Hammer Mead', below), though there is no evidence to confirm that the pig iron produced at Tilgate was processed at either of these sites. It is possible that Worth Furnace was serviced by these forges. So what's left to see of Tilgate Furnace today? The answer, when referring directly to the furnace and furnace pond is, unfortunately, not a lot. But there is a little bit to see if you look hard enough. As long ago as 1931, archaeological observers were noting that the bay had been virtually leveled and just a slight rise in the ground was now visible and a similar observation was made in 1952. Of course, most of the site of the bay has now disappeared under the 'cheese houses' of the Shrublands Estate, but if you follow the footpath south out of Laurel Close, cross the stream and then veer to the right towards Tilgate golf centre, glance to your right. Between the path and the rear of the Shrublands estate you will notice a low flat area and this is what remains of the silted up bed of the pond. To the north of the pond bed (to your right if you are facing it from the footpath) you'll notice a slight mound, no more than 5-10 metres long, and this is the last remains of the bay and/or pond banks. A small stretch of the footpath itself, which is raised above the pond bed, was the original waters edge. If you look at the map above, these features form part of the protruding semi circle in the bottom right corner of the pond. There are other, more noticeable, remnants of Tilgate Furnace remaining, however, and the most obvious and well known are the three supply ponds; Tilgate Lake, the Silt Lake and Titmus Lake at Tilgate Park. The main lake at Tilgate was repurposed after the furnace ceased production and a mill was in use between at least 1785-1840. remnants of this, and another possible mill, were found during the dam restoration in 2010.

Of course, to produce iron in the days before railways and the motorised transport there needed to be a supply of ore nearby and half a mile to the north west of Tilgate Furnace is Hawth Woods. Those familiar with the woods will also be familiar with the 'bomb craters' that are scattered throughout and these are 'mine pits' from which ore was extracted and rolled down the hill on sledges for processing at Tilgate Furnace.

Tinsley Forge, the destination for pig iron from Tilgate Furnace for over 40 years, was in operation from 1574 until 1736 and was located on the flat ground just to the south of where Cornwell Avenue, in the new Forge Wood (does the name make more sense now?) estate, now bridges Gatwick Stream. Little evidence now remains, besides the low flat area to the south of the road marking the site of the pond bed which, at the time of writing, seems to be the subject of building work as part of the new neighbourhood. From 1574 until his death in 1589, the forge was owned by Henry Bowyer. Records are sparse for most of the following century, but then it was purchased by Leonard Gale, a blacksmith from Sevenoaks. On Gale's death in 1690 the forge was passed to his son, also named Leonard who, in 1696, purchased the nearby Crabbet estate for £9,000! Gale is immortalised by the naming of Gales Drive in modern Three Bridges.

As expected, when we visited the site there wasn't much to see, but we did find some banking to the east of the pond bed and next to the stream which could have been used to contain the pond 450 years ago or may just be a more modern flood defence. The banking has several mature trees growing on it and has a recent drainage channel cut through too. It was in this area, in the bank of the drainage channel, that we found what appears to be a large piece of forge cinder.

Nearby, to the north of the pond site close to Radford Road and in a large private garden, are the hidden remains of a medieval settlement that was occupied continuously from the 12th century into the 18th century. It is likely that this settlement was home to those working at the forge and also, given it's age, points to the possibility that iron working was occurring on the site before the coming of the hammer pond. Bewbush blast furnace is first documented as being in operation in 1567 when it was sending sows of cast iron to Burningfold Forge, a little way south of Dunsfold in Surrey. This is quite some distance to transport half ton bars of iron when considered in the context of the roads and methods of transportation available at the time and the creation of Ifield Hammerpond (now Millpond) and Ifield Forge immediately downstream from the furnace was an endeavour of practicality and economics. The freehold of the Bewbush Estate, or the Manor of Bewbush, switched sporadically between Crown ownership and that of various members of the nobility, but the estate was leased to various lessees who would then sub-lease various constituent parts of the estate, such as agricultural land, homes, farms and… furnaces! The furnace was almost certainly constructed before 1563 by a gentleman called John Mayne who died in 1566, passing ownership to his son Anthony who is also documented as being the owner of Ifield Forge in 1608 when the leases of both sites were transferred to John Middleton. It is likely that Mayne Junior constructed Ifield on inheriting Bewbush, increasing the value of his newly acquired asset by providing a nearby forge and thus reducing transport costs considerably. Middleton held the lease to both sites until his death in 1636 when they passed to his son Thomas. In 1654 the lease of Bewbush Furnace and pond were part of a large conveyance of lands ‘in Bewbush & Shelley’ to Bray Chowne for £5,000, though the furnace had been disused for over a decade by this point, having most likely been destroyed by Wallers forces in 1643 during the Civil War. It is documented that this is the fate which befell Ifield forge, less than a mile to the north east, and this was confirmed during 2014 when works to repair the dam at Ifield Millpond revealed the charred remains of the forge between the current mill and the Millhouse - originally the ironmasters house. I have also been supplied with two independent anecdotal reports of metal detectorists unearthing Civil War era shot in the area around St Margaret’s Church in Ifield Village, but these finds have not been recorded anywhere. In 1653 Bewbush appeared on a list of working furnaces, but it is possible that this was based on outdated information, though it is equally possible that it had been brought back into production as it formed part of the transfer of land to Bray Chowne. Other sources, however, say that it is noted as ruined in the 1653 list. By 1664 the furnace was certainly ruined, and did not operate again. It was last recorded as being in production in 1642, but that doesn’t mean that production ceased at that time and there is no reason to not suspect that it was working until the point that the Parliamentarians, having emerged victorious from a battle with the Royalists on Ifield Brook Meadows, didn’t march for a further mile and destroy the furnace after burning the forge to the ground. We noted above how the lessees sub leased parts of the estate, so who actually operated the furnace? Mayne Senior granted Edward Fenner a 21 year sub-lease on the furnace who subsequently passed it onto his brother, Thomas. In 1567 or 1568 Thomas sold the lease to a Thomas Ilman of Ifield who then mortgaged it to Roger Gratwick (Senior) on 16 February 1569 for £74.13.4 (£74.67). On Gratwick’s death in 1570 his son, also named Roger, inherited the lease. Title to the lease then gets a little messy as Ilman was heavily in debt and known to have been defrauding both friends and business associates. Evidently the mortgage was never discharged as by 1574 the lease was back with the Ilman family, now with Richard (presumably the son of Thomas) and his business partner Ninian Challinor. The next recorded change of ironmaster doesn’t occur until 1608 when the estate lease holder, John Middleton, also operated the furnace. On Johns death in 1636 his heir, Thomas, employed Walter Burrell & Jeremiah Johnson as ironmasters. Regarding the Middleton family, this is where the fate of the furnace (and indeed the forge, as the lease to both sites was owned by the Middleton family) becomes something of a paradox. John Middleton (b. after 1558, d.1636) of Hills Farm Place was the MP for Horsham, a constituency of which the Crawley area was a part, from 1614-1629. Parliament was then suspended for 11 years by King Charles I and by the time that the House was re-instated in 1640, John had died and the seat was taken by his son Thomas (b.1589, d.1662). Being an MP, Middleton had to be seen to be supporting Parliament when the Civil War broke out, but he harboured Royalist sympathies and his forge at Ifield, the freehold to which was Crown property at the time, was involved with the supply of ordnance to his landlord, hence its destruction by the troops of Sir William Waller. Middleton was later charged with aiding the Royalists, but the charges were not proven. He was re-arrested in 1648 following a Royalist uprising in Horsham, despite remaining as Horsham’s MP. As discussed above, the furnace is last documented as producing iron in 1642. Many sources put this down to a lack of fuel as a result of the forests of Bewbush and Shelley having been badly managed and being totally stripped of timber, though I tend to favour the theory that it was deliberately destroyed. The lack of timber theory undoubtedly derives from records showing that in just a seven year period from 1589 56,000 cords of wood, worth £4,200, were logged across Bewbush and Shelley for use at Bewbush and Ifield. A cord in Sussex at the time is recorded as being 126 cubic feet of dry wood, which would have weighed roughly a tonne.

The pond was situated in what is now the north eastern corner of Kilnwood Vale, tucked up against the southern side of the railway line and was larger than that at Ifield Forge (now known as Ifield Millpond) when in its prime, but you can see from the maps as we gradually move forward in time that the pond gets progressively smaller up to 1954, when the Ordnance Survey map shows the area as marshy land. In recent years it has been a landfill site, but until as recently as March 2019 some of the outline of the pond was visible from the air. This is no longer the case as the Kilnwood Vale development creeps north towards the railway line and it has now been almost completely obliterated.

When the estate lease was sold to Bray Chowne by the Middleton family in 1654 they included a furnace that was either in ruins or had been rebuilt. The furnace was certainly noted as ruined by 1664, I think it is probable that the list of 1653 was based on outdated information or has been misconstrued. At some point after 1664, on the site of the furnace, a grist mill was constructed. A grist mill was a mill where local farmers brought their own grain which the miller then ground and returned to them as flour, minus his percentage; The Millers Toll. Dating information on Bewbush Mill has so far proved pretty elusive, but an idle pond would not have been desirable for Chowne and it is therefore likely that the mill, or a mill at least, was constructed soon after this time; as a point of reference the first mill at Ifield was operating within 17 years of the forge being destroyed.

With so little information available, it is impossible to date the mill, but it seems reasonable to suggest a build date of perhaps sometime in the 1670s unless the pond was allowed to lay idle for decades. The earliest documented existence of the mill is 1787, but this doesn’t mean that it wasn’t in operation before this date. A precise year that it ceased to work has also proved elusive, but by using old maps, which were considerably more detailed by the 19th century, it is possible to date the its demise as a working mill to somewhere between 1841 and 1874. Further investigation has unearthed documents pertaining to the construction of the Three Bridges to Horsham railway from 1838 (see Were there any other buildings in the area) which name the miller, and resident of nearby Pondside Farm, as Henry Stepney and the owner of both properties as Thomas Broadwood of Holmbush (See The Buildings & History of The Manor of Bewbush). Stepney died in the 3rd quarter of 1842 and Broadwood in 1861. By this point in time the build-up of 300 years of silt would have diminished the strength of the water flow onto the wheel, negatively affecting the efficiency of the mill, and dredging would have been a costly exercise, so did one of these deaths spell the end of the road for Bewbush Mill? We can say with a high degree of certainty that Stepney’s death wasn’t the end of the road as the 1851 census lists the uniquely named Thornville Royal Knight as being a miller at Bewbush Mill. We also know that the death of Thomas Broadwood, on 6 Nov 1861 didn’t prompt its closure, as the census of 7 April 1861 shows the resident of the mill to be Thomas Pickford, whose occupation is listed simply as farmer; there was no longer a miller at the time of Broadwoods death. A miller is said to have been noted in the Bewbush area in documents dating from 1862, but details are vague and the record probably refers to a windmill, as the Tithe Map of 1841 shows a field called ‘Windmill Field’ to the west of Bewbush Manor House. Perhaps this windmill was built to replace the water mill? So we can, with confidence, date the closure of Bewbush Mill to sometime between 1851 & 1861. The mill building was subsequently

demolished in 1931 while the pond itself remained in water well into

the 20th century and was eventually allowed to drain and silt up

shortly after the Second World War. It was later used as a landfill site

for inert waste as Crawley New Town developed and is now

disappearing under the Kilnwood Vale development, though current

plans suggest that some of the area of the pond, at least, will be

designated as ‘parkland and open space’. The tail end is earmarked

for ‘office space’. So what can we view today? Whilst the pond is now gone the 275m long bay is still very much in existence and you may well have walked along it without realising as it forms part of the path from the foot crossing over the railway at the end of Kilnwood Lane/Mill Lane towards Bewbush West playing fields. If you walk along this bridlepath, look down. At most times of the year (autumn excepted, when the path is covered in leaves), you'll notice that the path is metalled with fist size lumps of iron slag. It is likely these were laid and compacted when the furnace was in operation in order to support the weight of the carts visiting the site to deliver the charcoal and ore and to take away the iron. The bay, when constructed, dammed Bewbush Brook and caused the flood plain in the shallow valley to fill with water, creating the pond. What we can also see is the likely source of the ore. A narrow seam of Horsham Stone runs roughly parallel with, and to the north of, the railway line and there is a string of large pits and quarries running along this seam. The 2-3 metres deep bed of Horsham Stone was no good as ore - it was used for paving and roofing - but the seams of stone are known to cover a particularly rich ore. Hawth Woods, the ore source for Tilgate Furnace, also sit atop a bed of Horsham Stone.

Many of you will be familiar with the point on this bridle path where the stream goes through a sluice gate; a survivor from when the pond powered a corn mill rather than the furnace. The area at the foot of the steep drop on the Bewbush side of the path is where the water wheel, which powered the bellows, would have been housed along with the furnace itself. In later years, this is where the mill stood. If you climb down the banking you will notice the remains of old brick walls against the bank and like the sluice, the walls are a relic of the corn mill, rather than the furnace, though well hidden behind years of vegetation growth is a wall that is made not of brick, like the old mill wall, but of lumps of rough cut stone. Is this the remains of the furnace, perhaps? Two the south of the wheelpit is a reported slag dump which I am yet to examine. Another surviving artifact from the mill is what appears to be a some form of rotating stone embedded in the ground with a tree growing around it.

Ifield Forge began production in 1569 on the site of an older medieval bloomery which was discovered on the pond bed when it was drained during recent renovations to the bay. A small valley was dammed at a point just downstream of where tributaries of the River Mole (Broadfield Brook, Bewbush Brook and the Douster Brook) converged in order to create what we now know as Ifield Millpond. The forked tail of the millpond illustrates how the two sets of streams came together, maybe just downstream of the island. The pond was originally much larger with the south western fork encompassing what are now the water gardens in Bewbush. The pond was not split in two by the railway line until the mid 1840's.

From 1574, the forge was owned and run by Roger Gratwick, who also controlled Bewbush Furnace and from 1608 both sites were owned by John Middleton. The site was mainly used to cast ordnance for The Crown and was burned to the ground by Sir William Waller's Parliamentarian troops in 1643 during the English Civil War and was not used as a forge again. What are believed to be the remains of the forge were found during the recent renovations, roughly between the primary and new spillways are, and the area of the stone work also contained a layer of ash, indicative of a fire which gives us some insight into the destruction of the forge. The archaeological report on the excavation is eagerly awaited! The position of the forge suggests/confirms that the current Ifield Brook, a man made channel until a few hundred yards north of the Church (see the Non designated heritage assets west of Ifield page for discussion on this subject and how the current mill race was originally Ifield Brook), was dug to serve the race of the forge. A corn mill was erected on the site by 1660 and a larger building followed in 1683 after the first was damaged or destroyed by fire. Both were owned by the Middleton family. The 1683 building was demolished and rebuilt in approximately 1817, leaving us with the restored building that we see today. The mill ceased to be a commercial concern in 1925. The Mill House, until recently a public house which has now reverted to a private dwelling, was built in the late 1500's as a home for the blacksmiths and later the millers who worked at Ifield.

Today there is not much left to see of the original forge features, but the pond, the 140m long bay, the Mill House and the restored mill of 1817 (which opens to the public and can be seen working on the occasional Sunday between April & September - see here for opening times) are still in existence and a plaque from the 1683 mill, including the date and the initials of Thomas and Mary (nee Goring) Middleton which was incorporated into the 1817 mill, is visible on the wall to the right of the entrance. Also left on site is a mitre shaped stone with a hole drilled through it, which I am yet to photograph, and this is thought to be a counterbalance for the forge bellows. Downstream of the bay, the walls on the northern side of the mill stream are constructed with large lumps of slag and reused bricks, though it is not clear if the bricks were sourced from the original forge or from one of the first two flour mills. In 2015 the entire area underwent a renovation as the bay was in a poor state of repair which placed the houses in the nearby Millbank under threat of serious flooding. The pond was drained and the whole area was landscaped and designated as a local wildlife site (see here for details). A boardwalk, visible on the aerial photos above, was added to the southern (Gossops Green) side of the pond and the paths were upgraded.

The Hyde Hill site, in Hyde Hill Woods to the west of St Andrews Road & Birkdale Drive in Ifield West, is a bit of an anomaly and it was hard to decide where in this article to place it, if indeed to include it at all. Having previously included it here I have now decided, due to the lack of evidence that it ever was an iron site, to remove it from this page. A full study of the site can be viewed on the Non designated heritage assets west of Ifield page. In use from approximately 1546 until 1617, Worth Furnace was the earliest, largest and most important iron works in the area. Worth was a double furnace built by William Levett on behalf of the Crown on land confiscated from Thomas Howard, the third Duke of Norfolk and uncle to both Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard. From 1547 cannons were cast on the site, as well as raw iron sows, and in 1550 the site was leased to Clement Throckmorton who paid the rent in the form of cannons and shot, rather than the £90 p.a. which would have been due. The land was returned to the Duke of Norfolk in 1553 when he was released from the Tower of London following the death of Edward VI and accession of the Catholic Queen Mary. The furnace continued to produce arms which were delivered to the Office of Ordnance in Southwark by Sir Richard Sackville who was a Sussex MP and later Chancellor of the Exchequer. By 1574 the furnace site was owned by Lord Abergavenny and leased to John Eversfield. In 1580 the rent due was just £10 p.a, compared to the £90 p.a. payable 30 years earlier, which suggests that the productivity and/or profitability of the site had declined significantly. Accounts from the state records show from Christmas Eve 1549 the furnace produced 156 tons of iron, 56 tons of cannons and 52 tons of shot with a total value of £1,973 3s, 1d. This volume of iron produced from, presumably, a years work illustrates the significance of Worth Furnace at this time. The raw iron produced here would have been taken to local forges, most probably those at Blackwater and Hammer Mead in what is now Maidenbower.

The remains of Worth Furnace can be found just east of the London to Brighton mainline railway at the point where the ancient Horsham to East Grinstead trackway crosses the railway at the end of Parish Lane. A little way to the north of the trackway, the 60m long remains of a large pond bay 2 - 3 metres high are immediately visible with Stanford Brook cutting through the dam. To the south of the bay, back across the trackway and beyond, the flat marshy remains of the pond bed can be easily picked out, especially during winter and early spring when the vegetation is lacking, and this is clear to see as you descend from the railway bridge, as well as from the bed itself and from the summit of the bay.

The stream itself, for several metres downstream from the bay, is littered with lumps of furnace slag, both large and small. The bay and pond were most likely larger than the remains that we can see today until the construction of the railway line in the late 1830's obliterated the western side. The furnace itself was located just to the north of the bay, towards the western end of the remains and earthworks in this area suggest a watercourse towards a depressed wet area 5m west of the current stream which was most likely the wheel pit, with a shallow ditch running north from it being the tail race.

In use from 1549 until 1617 Blackwater Forge was probably the hammer connected to Worth Furnace and this assumption is based on the cost of transporting a ton of iron sows from Worth to it's forge which was noted in accounts as being 8d (approx. 3p) and compares well with the cost of transporting the raw iron between sites that are better documented during the same period. Other documentation from the period mentions (translated to modern English) The making of three new bridges on the route from the hammer of Worth to Crawley which undoubtedly refers to the construction of the bridges which gave Three Bridges it's name. In the late 1980's, prior to the commencement of the Maidenbower development, excavations of the site were undertaken by the Field Archaeology Unit of University College, London. This project confirmed that the site was a post medieval forge and discovered the timber remains of two tail races (the exit point of the water after it has driven the wheel), double wheel pits and an anvil base. Photographs of the excavation and discoveries can be viewed on the Wealden Iron Research Group website.

The site is on the bridleway known as 'The Bower' in Maidenbower. Walking down the hill from Blackwater Lane into Maidenbower, under Worth Way, the 140m long remains of the bay, which reaches heights of up to 2.75m, start on your right, just before you reach the bridge which crosses the stream, and then continue both underfoot (the bay forms part of the bridleway) and in the form of a mound to your left. The remains of the pond itself are to your left behind the bay and can be seen as flat land, though most of the pond site now plays host to the houses of Westminster Road, Dollis Close & Campbell Road. To your right, towards the southern end of the bay, is a small stagnant pond and this is the site of the wheel pits. Forge waste, in the form of slag, can be seen in the stream.

Probably connected to Worth Furnace, Hammer Mead was probably a forge site in the woods to the west of Brook Infants School in Maidenbower. No visible traces of the site remain and the only clues to it's former use are a few pieces of forge cinder discovered in the stream during a survey in 1971 and the name of the site, Hammer Mead, taken from the 1841 Tithe Map. Based on the topography of the land, the pond was likely to have been in the dip in the area of Salterns Road, Stopham Road and Moorland Road. In use from 1556 to 1653, there is not much information available and as such it is unclear from where Rowfant sourced it's raw iron. When iron production in the area ceased, Rowfant pond, like that at Ifield, was used to power a corn mill. The mill, which ceased working in the early 1930's still exists as a private residence, along with the pond and the 100m long bay, which carries a private road and bridleway. It is likely that the mill was built on the site of the forge.

Sources:

Text & photographs © Ian Mulcahy. Contact photos@iansapps.co.uk or visit my 'Use of my photographs' page for licensing queries (ground level photographs only). Lidar imaging © OpenStreetMap contributors and https://www.lidarfinder.com/ |

pictures taken with and and |